erika vancouver

les petites-filles de Salvatore*

«Il a fallu quitter ma terre

Ma femme

Mes enfants

Mes parents

Mes amis avec un déchirement profond»**

Salvatore Gucciardo

8th August 1956. Exactly sixty years ago. Bois of Cazier, Marcinelle, in the municipality of Charleroi, in the province of Hainaut, a region of the Wallonia, Belgium. A cloud of smoke rises in the sky and surrounds the mine, announcing to the world that one of the greatest industrial disasters in history is unfolding. Just before that was the strike of a hammer, the signal that the lift can go back up to the top of the shaft. But the go-ahead was not given. Down there the miners were still putting a cart inside the lift. Part of it is still out, while from above the lift is trying to be hoisted up, everything is torn out: pipelines, electric cables, the compressed air pipe. A fire breaks out. The lift is blocked.

Human error, determine the experts. An error, which leaves no way out to those who in the bowels of the earth will die there. The bodies remain at almost 1000 metres in depth for two weeks before the rescuers can reach them. The body count is impressive: 262 men, of which 136 Italians.

But why among the victims of a disaster in Belgium are more than half (just under 53%) Italian workers?

At the end of the Second World War the Belgian population, returning from the horrors of the conflict, tend to refuse work in the mines, so much so as to put at risk the continuation of mining. The government seeks then a solution by making international agreements. In June 1946 a pact of exchange is signed with Italy (work force against coal), which foresees the transfer of 50,000 workers to Wallonia. They are guaranteed accommodation and training courses. The reality though is quite different. The living quarters are often barracks built during World War II and the local population cannot be said to be alien to manifestations of racism.

Nevertheless, thanks to the situation of an Italy, which was literally left in pieces from the Second World War, entire trains full of emigrants leave for Belgium. It is estimated that a thousand workers a week arrive at the mines. Young people who leave their land and their families with the illusion of a better life. But history teaches us that, between 1946 and 1955, more than 500 Italian workers instead of a better life will find death in the Belgian mines.

The tragedy of Marcinelle anyway produces a double effect. On the one hand it marks the end of the agreements on coal between Italy and Belgium, and, on the other, begins the transformation of the relations between the local population and Italian immigrants, who in the seventies have become the first foreign community, arriving at a count of approximately 300,000 individuals integrated into Belgian society.

Some twenty years later, precisely in 1991, with the intent to «honour the Italian immigration» (an operation in itself praiseworthy, but that probably could have been conducted following a criteria of other profundity) is held the first

Miss Italy in the World contest. The Italian community in Belgium ends up being involved in this regurgitation of national popular identity. Since the beginning of the event there are in fact as many as 30 candidates who come from Brussels, Charleroi, Mons, La Louvrière and Liege. A thread so thin and questionable re-establishes the connection to the land of their grandparents.

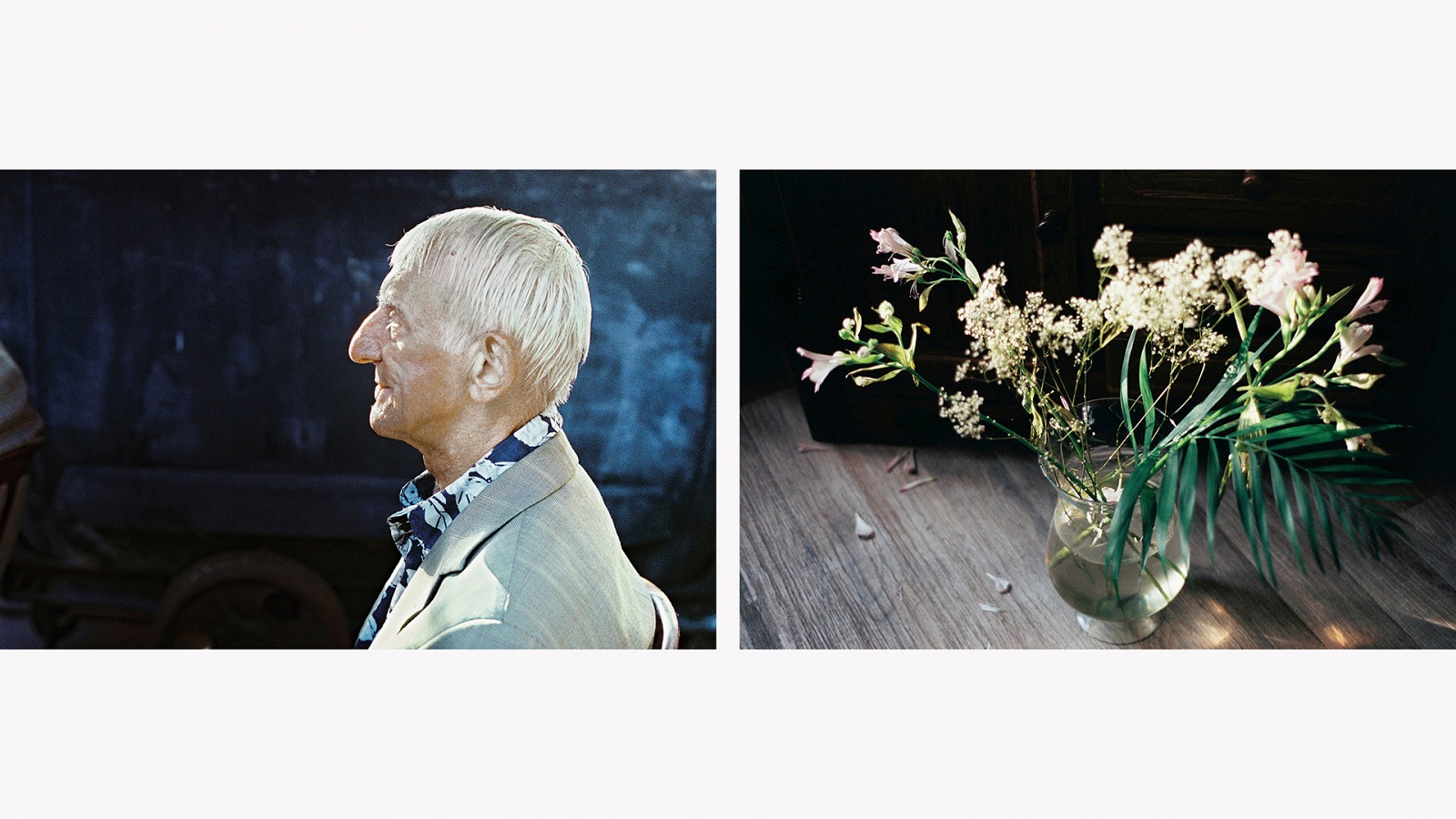

To form a profile of the communities of Italian origin living in Belgium today also means to keep in mind these stages of its evolutionary process. But today who are the descendants of those young men who every day sank into the bowels of the earth, where «if the lamp passes, the miner passes»? How to define their identity? To what extent do they feel Belgian? And to what extent do they feel Italian? Beyond the inheritance implied in the names, it is enough to simply enter their houses to hear the echo of a past. Old faded photographs build lay altars in a corner. From the shrivelled up faces of elderly Italians who scrutinise their offspring and keep alive the memory of a daily sacrifice, of broken families, the grief of married women often by proxy, of marriages coming to nothing in less than a month at a thousand metres below the ground.

The language, a bond that unifies the people, is not so strong here. Born and raised abroad, the younger generation may not even understand the grandparents when they speak. Moreover, among the elderly, many express themselves with a language in many cases even hostile to those who continued to live in Italy. Emigrated more than half a century ago, some of these Italians - as recent interviews with survivors of the tragedy show - still use the popular dialects spoken in their respective places of origin in the mid-fifties of the twentieth century. That transmitted by the language is anyway an identity, which clings to fragments of memory of an Italy, which no longer exists. An identity, which is certainly not easy to believe, can be identified by the younger generations born and raised in Belgium.

In all this emerges, powerful however the typical role of the photographic image, which consists in preserving and transmitting the memory. A role which winds its way on a dual track. On the one hand the collective memory that is based on images such as the cloud of smoke rising from the mine. Images, which are custodians of the documentary value of significant events. On the other, the iconic vernacular tradition which delegates the crystallisation of personal memories in the form of portraits, that inhabit the houses joining with other objects of the memory, as if they were a kind of contemporary

Lares familiares.

The vernacular tradition of photography superimposes then the watchful gaze of the author who collects with sensitivity the signs; real museum traces, and uses them to investigate the sense of identity of the community. The statue of the miner, the cushion on which is printed the photo of a couple, but also the simple reflections created by the vase of flowers on the table are signs that reconstruct the meaning of the search for an identity that is built, or rather

rebuilt, day after day. A look that, fixating on memories not experienced first hand, in some way makes them their own when paused on that mine, where once one dug and then died, while today there is tourism in the wake of a guide.

In the crucible project all these elements come together to give life to a palpable atmosphere that tell of a suitcase near a sixties style chair, tell of trips to Northern Europe, uprooted lives and the search for a new identity that also passes through the

sense of home and of integration that come with owning a fashionable chair at the time. But the identity is made of a past that somehow appears even among the ranks of a beauty contest, tenuous umbilical cord with a source for many of only an oral tradition.

Among the pale blue tiles of a changing room of the mine, an old frame still hangs on the wall. It is hard to say if it is a small painting consumed by time or, more likely, a corroded mirror. It is a corner in which to stop for a moment and recognise ones self. To remember, yesterday like today, where you come from.

[

Sandro Iovine ]

--------------------------------------------

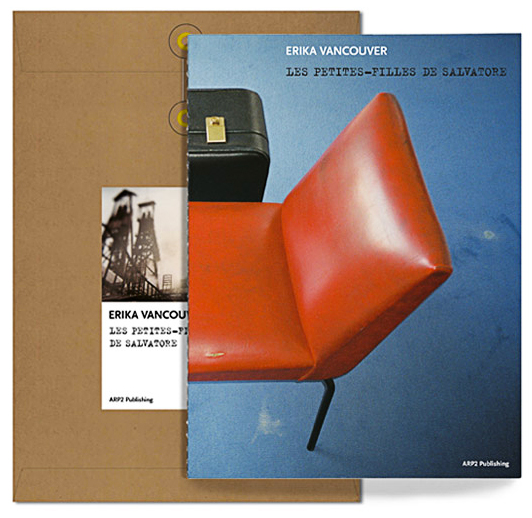

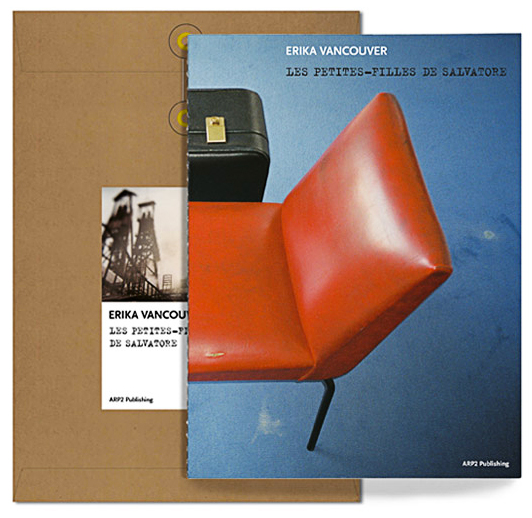

(*) - Les petites-filles de Salvatore (Salvatore’s grandchildren) is a photographic work that FPmag selected in Arles during the portfolio readings of Voies Off 2016. The project is on display until 4th December 2016 at the Musée de La Photographie of Charleroi in Belgium. The project is accompanied by a book of the same name (Les petites-filles de Salvatore by Erika Vancouver, with a poem by Salvatore Guicciardo, graphics by Dojodesign.eu, ARP2 Éditions, Bruxelles, 2016, Format: 56 pages 21,5x29cm, 41 photographs in full colour, inside a booklet and placed in a Japanese style envelope, circulation 300 copies, price € 30.00), which can be purchased at ARP2 Éditions.

(*) - Les petites-filles de Salvatore (Salvatore’s grandchildren) is a photographic work that FPmag selected in Arles during the portfolio readings of Voies Off 2016. The project is on display until 4th December 2016 at the Musée de La Photographie of Charleroi in Belgium. The project is accompanied by a book of the same name (Les petites-filles de Salvatore by Erika Vancouver, with a poem by Salvatore Guicciardo, graphics by Dojodesign.eu, ARP2 Éditions, Bruxelles, 2016, Format: 56 pages 21,5x29cm, 41 photographs in full colour, inside a booklet and placed in a Japanese style envelope, circulation 300 copies, price € 30.00), which can be purchased at ARP2 Éditions.

(**) - «It was necessary to abandon my land | My woman | My children | My parents | My friends with a deep sorrow» from

L'immigré by Salvatore Guicciardo in Les petites-filles de Salvatore, ARP2 Éditions, Bruxelles, 2016; p. 10. The Italian translation by Maria Teresa Epifani Furno (poet, writer, literary critic) is on p. 17.

_ _ _

[ INTERNAL RESOURCES ]

◉ [ FPtag ] Voies Off 2016

home

cover ▼

opinions

news ▼

portfolio

post.it

post.cast

video

ongoing

thematicpaths

googlecards

FPtag

home

cover ▼

opinions

news ▼

portfolio

post.it

post.cast

video

ongoing

thematicpaths

googlecards

FPtag

Erika Vancouver - She lives and works in Brussels. She graduated in 2009 with a Master in Fine Arts at the

Erika Vancouver - She lives and works in Brussels. She graduated in 2009 with a Master in Fine Arts at the